February 6, 2017 From rOpenSci (https://deploy-preview-119--ropensci.netlify.app/blog/2017/02/06/plater-blog-post/). Except where otherwise noted, content on this site is licensed under the CC-BY license.

As a lab scientist, I do almost all of my experiments in microtiter plates. These tools are an efficient means of organizing many parallel experimental conditions. It’s not always easy, however, to translate between the physical plate and a useful data structure for analysis. My first attempts to solve this problem–nesting one ifelse call inside of the next to describe which well was which–were very unsatisfying. Over time, my attempts at solving the problem grew more sophisticated, and eventually, the plater package was born. Here I will tell the story of how with the help of R Packages and the amazing reviewers (Julia Gustavsen and Dean Attali) and editors at rOpenSci, I ended up with a package that makes it easy to work with plate-based data.

Plates are great

Plates are great

Microtiter plates are essential in the lab. Basically an ice cube tray about the size of an index card, they have “wells” for between 6 and 384 ice cubes (up to 6144 if you’re a robot!). Except instead of freezing water, you use each well for a different sample or experimental condition.

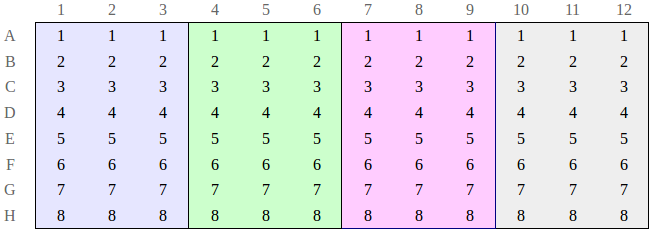

For example, say I have 8 samples and want to test 4 different drugs. Each drug should be tested on each sample three separate times to ensure accurate results. A 96-well plate is perfect for this: it’s a grid of 12 columns and 8 rows. So each sample would go in its own row. Each drug would then go in a group of three columns, say Drug A in columns 1-3, Drug B in columns 4-6, and so on. This is shown below, with the numbers 1-8 representing samples and the colors representing groups of wells treated with the same drug.

Typically, I make myself a map like the image above before I start the experiment, then I take it with me into the lab when I’m ready to begin. The map creates a powerful mental connection between each experimental condition and its particular physical location on the plate. With large effects, you might even be able to visually see the results of your experiment: all the cells in this column died, or the cells grew like crazy in that row.

This is very convenient to work with physically and remember mentally.

Plates are not tidy

Plates are not tidy

The problem is that you can pack a ton of complexity into a small experiment and mapping that back into a tidy framework for analysis isn’t always easy.

One way to map from data to plate is through well IDs. Each well has one. For example, the top left well is in row A and column 1, so its ID is A01. The well in the third row down and 5th column over is C05. But how do you say that everything in row A is sample X, everything in row B is sample Y, and so on?

My first strategy was to put it in the code, with a mess like this:

data <- dplyr::mutate(data,

Sample = ifelse(Row == "A", "Sample X", ifelse(

Row == "B", "Sample Y", ifelse(

...))),

Treatment = ifelse(Column %in% 1:3, "Drug A", ifelse(

Column %in% 4:6, "Drug B", ifelse(

...)))

)

But doing it this way made me want to cry.

My next strategy was to try to directly make a table and then merge it into the data. The table would look something like this:

| WellId | Sample | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| A01 | X | Drug A |

| A02 | X | Drug A |

| A03 | X | Drug A |

| A04 | X | Drug B |

| … | … | … |

| B01 | Y | Drug A |

| B01 | Y | Drug A |

| … | … | … |

While this merges nicely into a data frame and solves the problem of indicating what each well is, it’s actually not that easy to create by hand, especially in more realistic experiments with more variables and a more complex plate layout. Even worse, there is a substantial risk of typos and copy-paste errors.

plater to the rescue

The solution came from the plates themselves: store the data and mapping in the shape of the plate and then transform it into a tidy shape. Scientific instruments often provide data in the shape of a plate, in fact: you get back a spreadsheet with a grid of numbers shaped like your plate, with a cell for each well.

My first step was to write a function to convert one of those plate-shaped grids to a data frame with two columns: one of plate IDs and one of the numbers (machine read-out).

So now I could take a .csv file with plate-shaped data and convert it into tidy form and connect it with the well ID. It didn’t take long for me to start creating .csv files with sample and treatment information as well and then merging the data frames together. Now I could create plate maps really easily because they looked just like the plate I did the experiment in.

A package takes shape

A package takes shape

With time and feedback from others in the lab, I refined the system. Instead of creating separate files for each variable (treatment, sample, data, …), everything could go in one .csv file, with sequential plate layouts for each variable (say, treatment or sample). I started calling this the plater format and storing all of my data that way. These files are especially nice because they give an overview of the whole experiment in a compact format.

Eventually, I boiled it down to a small set of functions:

read_plate: takes aplaterformat file and gives you a tidy data frameread_plates: takes multipleplaterformat files and gives you a big tidy data frameadd_plate: takes aplaterformat file and a tidy data frame and combines themview_plate: takes a tidy data frame and displays selected variables from it back in plate shape

Is this thing any good?

Is this thing any good?

With the package in place, I started getting ready to submit it to CRAN, but I wanted to get more feedback first and rOpenSci seemed perfect for that.

It turned out that the improvements started even before I got any feedback. As I prepared to submit the package to rOpenSci, I went through their thorough guide to make sure plater met all of the requirements. This process made me aware of best practices and motivated me to handle niggling little details like using consistent snake_case, making sure all of the documentation was clear, and creating a code of conduct for contributors. In all, I made 22 commits preparing for submission.

The review process itself led to even more improvement. Two generous reviewers (Julia Gustavsen and Dean Attali) and an editor spent multiple hours reading the code, testing the functions, and thinking about how to make it more useful. Their thoughtful suggestions resulted in many changes to the package (I made 61 commits responding to the reviews) that made it more robust and useful. Among others:

- Make

add_platemore easily pipeable by reordering the arguments - Add a function

check_plater_formatto test if a file is formatted correctly - Brainstorm a Shiny tool for non-R users to use

plater - Explore alternative visualizations to

view_plate

The reviewing process made plater a much better package and left me feeling confident in putting it up on CRAN with a stable version 1.0.0.

Conclusion

Conclusion

Since transferring plater over to rOpenSci and putting it onto CRAN, I’ve used the package all the time and have shared it with lab mates and colleagues. It works well and does exactly what I want, seamlessly without my needing to even notice it. This level of convenience and utility is the best testament to the efforts of the reviewers and editors of rOpenSci, who helped to make it a better package.